This article discusses an interactive installation created at the Interaction Design Master in Malmö. The research phase used cultural probes to explore how people could retell each others’ life stories using drawings and collages. The experience of filling up the probes was meaningful and valuable for the participants, and we attempted to translate that experience to an embodied installation: a large wooden machine, similar to a printing press, augmented with many interactive behaviours.

User research provided us with a unique nugget of experience to explore. The conceptualization that followed as we tried to translate it to an installation was challenging but rewarding. I like how the result looks and feels low-fi and analogic, while actually having plenty of digital machinery inside. To this day, I’m not sure that we fully succeeded at translating the emotional experience that we were looking for, but the end result was surprising and very enjoyable.

Introduction

This project was carried out at the University of Malmö, following the brief Archiving the intangible. We used this as a starting point for an exploration on identity, memory and cross-generational communication. Our main focus was on storytelling and re-interpretation.

In an individual’s memory, the processes of organizing and remembering are subjective and depend on personal perception, experience and point of view: we try to impose meaning on what we observe, using what we can recall from our experience as a guide [1]. The building of personal archives is driven by motivations that go further than simply storing things for later retrieval: building them also pursues the goals of creating a legacy, sharing resources, reducing fear of loss, and expressing and crafting one’s identity with regard to others and to oneself [6]. People relate to a small number of mementos that are carefully selected and invested with meaning, thus creating a memory landscape of autobiographical objects around them [10].

Within the family, communication among generations takes place through a combination of implicit emotional language, imitated behaviour, spoken language, and writing [7]. In this context, archiving and retrieving are social shared experiences. There may occur conflicts between the communication models used by different generations: these differences have existed throughout history, but rapid cultural and technological changes have broaden this generational gap. Memory, identity, and cross-generational communication have strong social and tangible components. To talk about them at an individual’s level can not be done separately from the world in which that individual lives and acts. The social context and the artifacts through which interaction is conducted are embedded in the environment. In sum, we are talking about an embodied experience [3].

The above insights led us to the following design opening: “How can we embody a social experience engaging people across generations to reveal fragments of their identity?”

Research

Cultural probes were used to provide inspiration for design through subjective engagement, empathetic interpretation and a sense of uncertainty [5]. We carried out a collaborative process where a participant would write a story from their childhood by hand and store it in the provided box; this story would then be passed on to a second participant, who would use collage and crayons to illustrate it.

We took great care in designing the probes to provoke inspirational responses: they were handcrafted and presented in small cardboard boxes. Our use of rough physical materials and handwriting was aimed at providing a more personal and evocative experience [4]. The selection of images for the collages opted for the uncommon, the surprising and the nostalgic: pieces from art magazines, newspapers, maps, old encyclopedias… roughly cut and bound together.

The participants were eight people between 8 and 83 years old, who filled the probes at locations familiar for them. Each took on both roles, first writing down a story and then illustrating one coming from another person. Having to reinterpret somebody else’s personal tale required empathy and imagination, creating an emotional bond: we tried to replicate this rewarding experience in our design.

Design

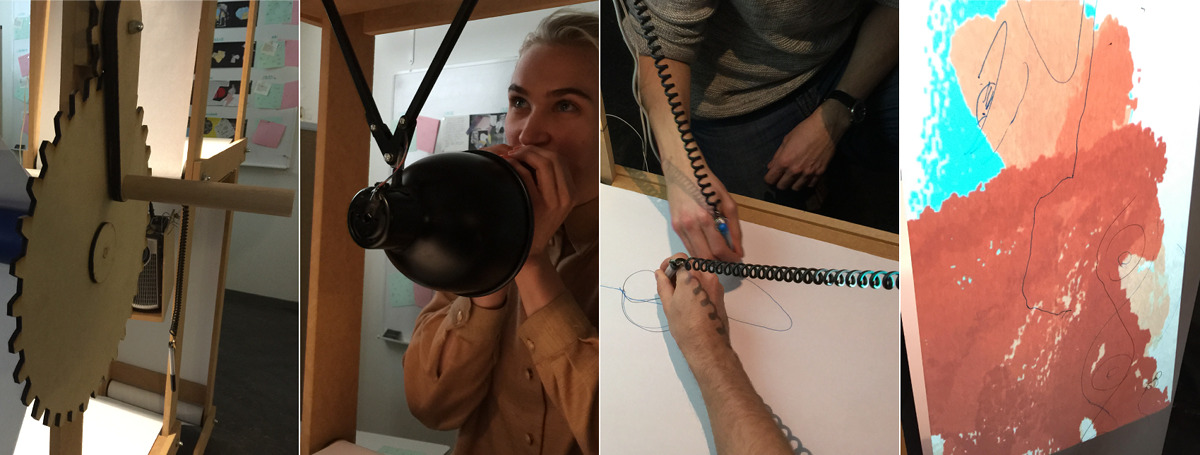

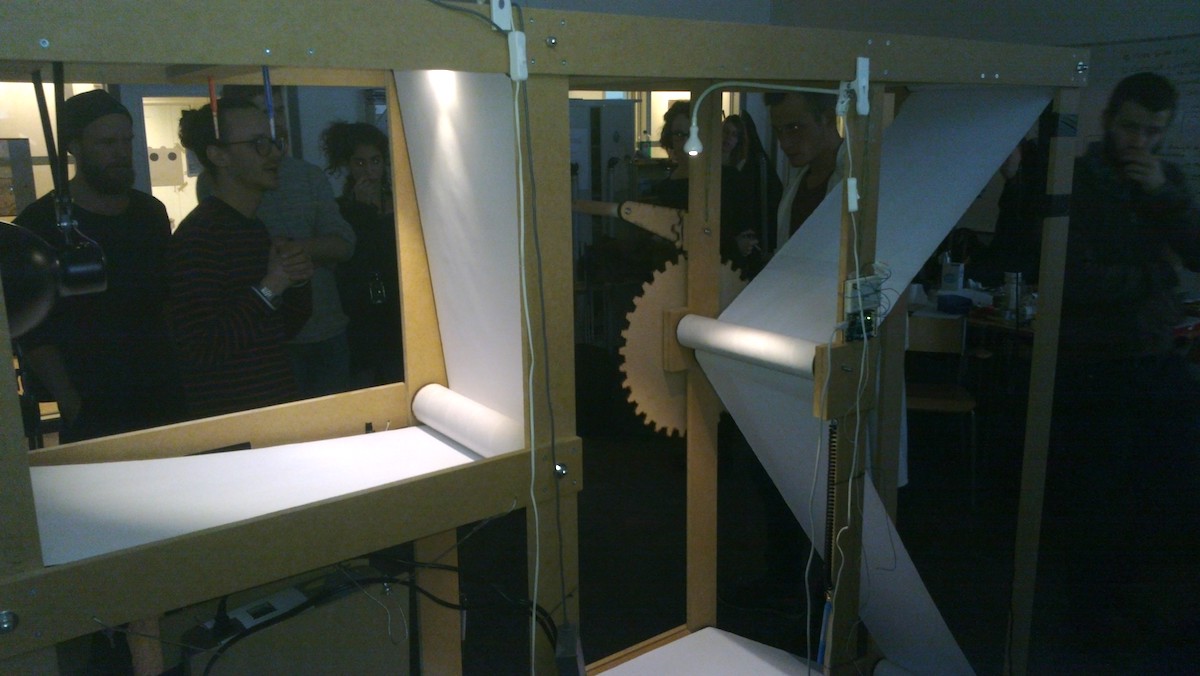

The previous findings led to the design and development of a physical prototype, which we called the Transgenerational Transmission Machine. This is a large wooden structure, holding a continuous strip of paper, and augmented through the use of sensors and actuators. This machine combined several metaphors that we found relevant for the communication of memories: paper as a storing material, a flow of mementos, infinite looping, and an aesthetic connection to the printing press.

We designed for a collaborative activity, so the machine would only work through the coordinated participation of several people. The roles of performer/narrator, participant and spectator [12] were clearly defined, but also flexible: our intention was that people could transition from one to another with ease. This keeps a certain relation to the concept of performativity [8], a process by which the necessity of audience enactment is taken into consideration; however, whereas the examples described in that piece of research use a pre-established narrative, here we simply provide a context for stories to be shared and enriched with the art generated by the audience.

The experience is embodied and requires participants to move around the space and use their bodies in different ways. The physical machine does not look like a regular digital device: as in the case of the cultural probes, the use of rough materials and the request for handcrafted creation are intended to be evocative, eliciting the remembrance of personal stories. Following that idea, we hid the presence of technology: the only explicit inputs are a crank, a microphone and a drawing area. To a first-time observer, the machine is remisniscent of a complex set of gears or a printing press; it is only by interacting with it and observing its complex behaviour that the technology supporting and mediating the experience becomes apparent.

Roles

The narrator tells a story to an intentionally large and whimsical microphone. In that position, her view of the rest of the machine is partially blocked, providing a small measure of intimacy that helps her focus on the tale. As she speaks, an Arduino-activated motor lets colored water drip on the paper. Currently, these narratives are improvised on the spot: future iterations contemplate the use of scripts or prompts.

The person operating the crank sets the machine in motion, and determines the speed and direction with which the paper will move across it. What initially had looked as a rather boring and mechanical task, was revealed during testing to be quite engaging.

Colour pens are provided for two participants to draw on the moving paper. Through the use of a capacitive sensor, the flat surface used for this illuminates when their hands are close. The location of this drawing area makes it most comfortable for children; however, its use by grown-ups has the benefit of providing a shared uncomfortable interaction that may benefit the experience [2].

On the other end of the machine, opposite the narrator, a projector is used on the paper: this projection comes from behind, so that it appears to observers as a sort of “live ink”. The movements of the participants are captured with a Kinect camera, and an computer program (developed with the OpenFrameworks toolkit) uses them to paint on the projected image. During testing, participants discovered that this particular set-up allowed for another mode of interaction: by placing their hands between the projector and the paper, they could create Chinese shadows that meshed with the colors drawn by the movements of people on the other side.

Using the terminology proposed by Reeves et al. [11], the spectator experience provided by our system is mainly expressive: manipulations and their effects are visible to the audience, enabling them to appreciate the performer’s interaction. Moreover, the use of coarse physical materials and the fact that most of the electronics are hidden aims to provide an experience that is also magical: it is not immediately apparent exactly how the effects are being created by the machine.

Discussion

This physical installation provided us with valuable insights on the interplay between narrator and audience, their changing roles, and the ways that physical and digital support can enrich this experience.

A contention point was exactly how much synchronisation among the users would be required. In our first version, the crank would make the machine work and at that point the other stations would operate independently. In a follow-up test, we made all the stations dependent on one another: the crank needed to be operated first, then somebody would have to speak into the microphone, then another person would draw, and only then would the Kinect projection come alive. In this second test, the experience was more frustrating: the interaction was not continuous but stuttering, and participants ended up doing bogus work (e.g. tapping on the microphone) to keep the machine working. Thus, an implicit call for collaboration seemed to work better than trying to enforce that collaboration.

The projection was able to ease the onboarding process by which a spectator would start taking part in the experience. This observation is consistent with other interactive installations using Kinect for grabbing the attention of people passing by; two factors at play here are inadvertent interaction and seeing others engage, both of which are powerful ways to attract attention and communicate interactivity [9].

Rough materials, “augmented paper” and tangible interfaces were powerful at drawing the imagination. We used digital technology to augment physical objects, but without letting it take central stage. Our machine aims to encourage playful, non-judgemental creativity, letting users discover new ways to interact (e.g. by integrating colour stains into their drawings, or by learning to make Chinese shadows). A measure of messiness and uncertainty can bring about unexpected, richer behaviour.

Movement and interaction create meaning and help us understand and manipulate the world around us [13]. In order to design for movement-based interaction, one has to move; in other words, purely theoretical work in not enough and the designer needs to be also acting and experiencing. Meaning is to be reached through rich, tangible interaction and movement, and this is applicable for the user as well as for the designer. Embodied interaction is a way to capitalise on a wider range of our skills, as well as to get human and social values back in balance.

One of our goals was designing for appropriation, allowing users to adapt the machine to make it their own. Alan Dix [14] describes the Technology Appropriation Cycle, according to which one should distinguish between technology-as-designed and technology-in-use: appropriation then becomes the process where one may turn into the other. These improvisations and adaptations show that users understand and are comfortable enough with the technology to use it in their own ways.

Conclusions

We used cultural probes to explore cross-generational communication through audience participation and re-elaboration. These insights led to the design and development of the Transgenerational Transmission Machine, a large physical device for collaborative storytelling and re-interpretation. Testing the machine offered a number of insights about the importance of the physical user interfaces for emotional relevance, the different roles among the participants in the experience, the need for prompts or cues to elicit compelling stories, and the value of embedded interaction to bring about emotional and evocative collective experiences. We are interested in finding other contexts where we could provide a similar experience around collaborative storytelling and re-interpretation.

I would like to thank my colleagues Martin Krogh, Isabel Valdés, and Ida Pettersson.

References

- [1] A. Baddeley. Your memory, a user’s guide. 1982.

- [2] S. Benford, C. Greenhalgh, G. Giannachi, B. Walker, J. Marshall, and T. Rodden. Uncomfortable interactions. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conf. on Human Factors in C.S., pages 2005–2014. ACM, 2012.

- [3] P. Dourish. Where the action is: the foundations of embodied interaction. MIT press, 2004.

- [4] B. Gaver, T. Dunne, and E. Pacenti. Design: cultural probes. interactions, 6(1):21–29, 1999.

- [5] W. W. Gaver, A. Boucher, S. Pennington, and B. Walker. Cultural probes and the value of uncertainty. interactions, 11(5):53–56, 2004.

- [6] J. Kaye, J. Vertesi, S. Avery, A. Dafoe, S. David, L. Onaga, I. Rosero, and T. Pinch. To have and to hold: exploring the personal archive. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conf. on Human Factors in C.S., pages 275–284. ACM, 2006.

- [7] S. Lieberman. A transgenerational theory. Journal of Family Therapy, 1(3):347–360, 1979.

- [8] A. Morrison, A. Davies, G. Brečević, I. Sem, T. Boykett, and R. Brečević. Designing performativity for mixed reality installations. FORMakademisk, 3(1), 2010.

- [9] J. Müller, R. Walter, G. Bailly, M. Nischt, and F. Alt. Looking glass: a field study on noticing interactivity of a shop window. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conf. on Human Factors in C.S., pages 297–306. ACM, 2012.

- [10] D. Petrelli, S. Whittaker, and J. Brockmeier. Autotopography: what can physical mementos tell us about digital memories? In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conf. on Human Factors in C.S., page 53.

- [11] S. Reeves, S. Benford, C. O’Malley, and M. Fraser. Designing the spectator experience. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conf. on Human Factors in C.S., pages 741–750. ACM, 2005.

- [12] J. G. Sheridan, A. Dix, S. Lock, and A. Bayliss. Understanding interaction in ubiquitous guerrilla performances in playful arenas. In People and Computers XVIII-Design for Life, pages 3–17. Springer, 2005.

- [13] C. Hummels, K. C. Overbeeke, and S. Klooster. Move to get moved: a search for methods, tools and knowledge to design for expressive and rich movement-based interaction. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 11(8):677–690, 2007.

- [14] [2] A. Dix. Designing for appropriation. In Proceedings of the 21st British HCI Group Annual Conference on People and Computers: HCI… but not as we know it-Volume 2, pages 27–30. British Computer Society, 2007.